Scaling Up Continuous Deployment

Continuous Deployment is for small startups who don’t care about quality. If I could sum up every misconception of Continuous Deployment in one sentence, that was it. Today I hope to dispell the “It doesn’t scale” myth.

Your build pipeline must scale up as two major factors increase: number of developers and number of people. When I say “scale up”, I very specifically mean maintaining the availability and performance of the system and keeping developers happy. All three of these factors are important and should be measured.

Firstly, set an SLA for your build pipeline, for instance I should be able to commit/deploy 99% of the time. Secondly, set a fixed goal for the total commit-build-deploy process. At IMVU that goal was roughly 10 minutes, at Canvas that goal was 5 minutes. If you set the bar high to start, you’ll maintain the benefits of fast deploys as you scale. Finally, and this deserves it’s own post, happiness. Track happiness explicitly via regular anonymous surveys, and make sure you fund the “little things” that frustrate everyone. It makes a huge difference, and ensures that down the road your system won’t have the usual “death by 1000 annoyances” that makes internal systems so painful to deal with.

Once you have your targets well defined, then it’s time to lay down the fundamentals. Scaling up Continuous Deployment starts with making your tests crazy fast. Step one in fast tests is write the right type of tests in the first place.

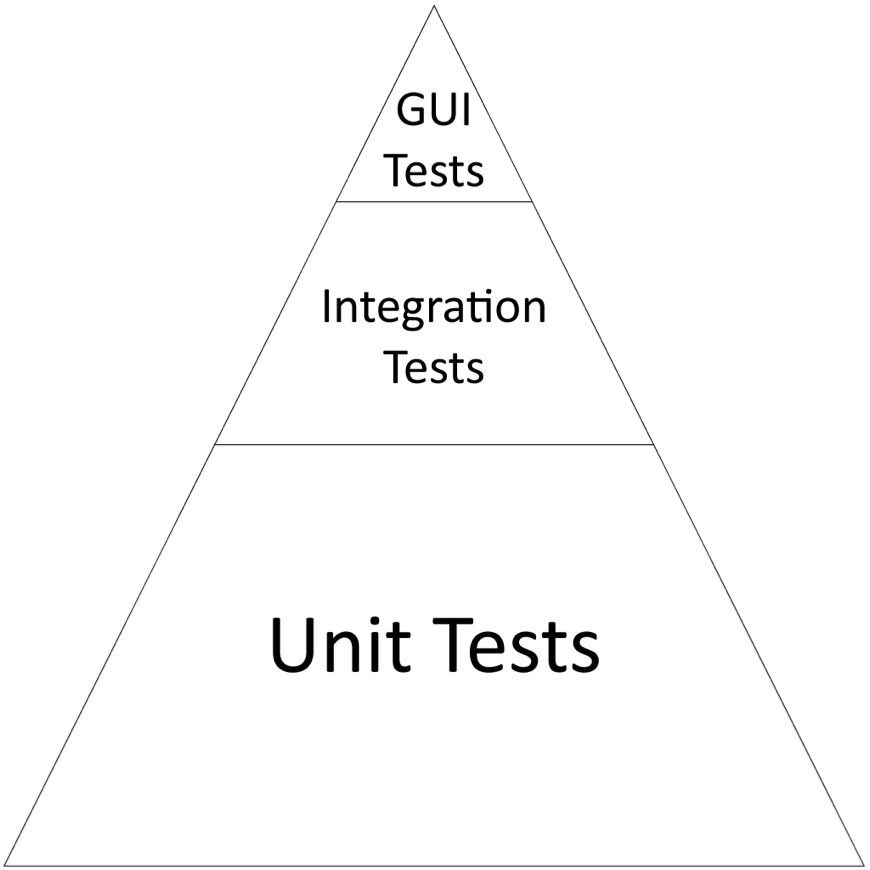

I think of it as a food pyramid of testing:

The important idea here is that most functionality shouldn’t be tested via end-to-end GUI regression tests. You must be sparing, or your tests will not just end up slow but brittle by virtue of the fact that they integrate with too much and do too much. For web apps this means be sparing with the use of Selenium.

Next up are integration tests. If your test hits the database, it’s an integration test. If your test makes an HTTP request, it’s an integration test. If your test talks to other processes, it’s an integration test. The simple fact is that most web testing frameworks only do integration tests, and most web developers end up writing way too many of these.

Finally unit tests. This should be your bread and butter. I may be bastardizing the term “Unit Test” since I don’t care about how many classes they touch, I just mean they don’t touch external state and they don’t rely on a specific environment. That means they don’t use randomness or time either. If you follow those rules it’s actually hard to write a test. You should be able to run thousands in a few seconds.

For every 1 GUI test, you want a couple integration test and dozens of unit tests. The only way to maintain a ratio like this is to conscious at all times of writing the right type of test for the functionality you’re testing.

Now that you’re making sure your individual tests are fast, you need to ensure that you’re running the test as fast as possible. Luckily running tests in parallel is usually straightforward. For unit tests you can just run multiple processes, or maybe your test runner has a multithreaded option. For integration/regression tests things get more complicated, and it usually makes sense to run them across multiple machines to ensure isolation. It’s fairly straightforward to use Buildbot or Jenkins to orchestrate multi-machine builds.

So now you’ve got the right kind of tests (fast ones) and they’re running in parallel across numerous machines. Just throwing hardware at the problem will work for a while, but eventually you’ll run into the hardest problem of scaling continuous deployment: The number of tests for a project is a function of the total man-months of engineeering. If you’re constantly growing the team over time you’ll end up with a geometrically increasing number of tests. Tests that all need to be run in a fixed time window. Except, to keep your SLA you need to keep the build from breaking. But the build is broken more often the more engineers (and thus commits) you push through the system. So now you actually need to shrink the build time so that bad builds can be reverted faster.

From my experience, if you’re writing enough tests you’ll want to start running them in parallel fairly early (2-4 developers) and after that you can roughly throw hardware at the problem until the 16-32 developer range. At that point, you’ll need to start changing the process in a more fundamental way.

Developers implicitly understand which commits are more likely to break the build. Usually there’s not much that can be done with that information, other than being more nervous when committing. A “try” pipeline is a system which builds patches or branches instead of the mainline trunk. Try pipelines can be used to test riskier builds without interfering with the main build pipeline at all. They cost a little: developers have to think to use them, and then that specific commit will take twice as long to ship. In exchange you can dramatically drop the number of broken builds. Buildbot directly supports this concept, and the only significant cost is the extra hardware to do parallel builds.

Along the same lines, you can have a bot watch for broken builds and revert-to the last succesfull build. The upside is that the system can bring itself back to good (able to accept good commits and deploy them) faster than a human could. The downside is that it’s fairly rude: anytime multiple authors get bundled in a broken build they’ll all suffer for one bad commit. Alternatively, you can commit to branches that your build system then merges for you once the branch individually has passed tests. This means the trunk build is never red, and no commit is ever rejected unfairly. Unfortunately it also means you’ll need significantly more hardware to run your tests.

Finally, you’ve written fast tests, have a try server or something more advanced but things are slowing down and getting frustrating. What do you do? The most common thing I’ve seen (explicitly or implicitly) is simply committing less frequently. This can take the form of switching to feature branches (and thus trunk is only merges of larger batches of commits), or team branches. Either way, you’re losing some of the advantages of Continuous Deployment. Maybe that’s the right trade-off for your team, maybe it’s not.

Conversely, the gold standard for scaling up continuous deployment is to simply make sure each team gets their own independent deploy pipeline. This effectively requires service oriented architecture for web applications, and so it may be a big pill to swallow depending on your existing architecture. It works. It can scale to hundreds or thousands of developers, and each developers is still able to have an incredibly fast deploy pipeline.